Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world,

Like a Colossus, and we petty men

Walk under his huge legs and peep about

To find ourselves dishonorable graves.

William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar.

No other shirt number in the annals of football carries such weight as the number nine, and few players have been as lauded as they who wear it. With misty eyes we tell stories about them; from Steve Bloomer, who was interned in Berlin during the first world war but who the fans of Derby County still sing about to this day, to Alfredo di Stefano, who scored in five European cup finals, and was on the winning side each time, to Gabriel Batistuta, once Argentina’s highest ever goalscorer, whose nickname told of what he did, what he lived for and what he gave to the world. Batigol.

This is a story about another number nine, and though he’d never be considered amongst such hallowed company, he is redolent of a certain era, a certain style, and a certain type of player. He’s a man playing at an old fashioned football club, in an old fashioned variant of an old fashioned role.

Sebastian Polter is a striker.

But first we must go back to Wilhelmshaven, where Polter was born in 1991 (not that he pronounces it Wilhelmshaven, with all of those jarring consonants crashing inexpertly against each other like waves against the dockside of a boring harbour town. He says wil’mshafn with one sound, two syllables.) It’s in Niedersachsen, seventy-something kilometres north-west of Bremen. It’s a big town, but it would be charitable to say that it’s probably not the most exciting place on earth.

I know. I grew up in a port town as well, and if you avoid getting into drugs, don’t fancy the police or the army, and have the luck that God gave you to dodge the bullet of a lifetime’s pushing paper around a shipping office, then it doesn’t leave many other options. He could have been a trucker or piloted a tug or a crane. And maybe he’d have liked it – he does seem to have an exhaustive knowledge of the logistics needed in the freight industries of northern Germany – but many wouldn’t. “It’s difficult,” he says, safe in the knowledge that he loves his home town, it’s what forged him, but that he also knows he had to leave.

And a lifetime in academia hardly beckoned. Polter didn’t hate school, far from it, but he wasn’t a natural either. Indeed, he answers the question of whether he was a good student with another question. “Well, it depends what you mean by a good student?” He was already falling behind not long after he’d started. There was just too much other stuff going on, what with trying to become the best goalkeeper in Germany. School was way down a long list of the young Polter’s priorities.

And they say he was a superb keeper, too. He’d been playing there since he was first able to, in the garden and the park, and then at SV Wilhelmshaven. He spent his days thinking about being the next Oliver Kahn, and his nights sleeping under the Kahn bedclothes he’d been given one Christmas. By fourteen he’d already spent a year at Werder Bremen and was being talked of being a selection for Germany sides. But it wasn’t as much fun as it was supposed to be. He felt a desperate need to be a part of the action, and if he was going to have to dedicate as much of his life to football as he would have to, it might as well be enjoyable.

Because that year playing in Bremen had been a slog. He’d have to travel there and back from Wilhelmshaven every day during the week. His days would be spent from dawn til dusk going to school, wolfing down his lunch before the long drive to training. Then playing. There was barely time for anything else. Like being a kid. Then, after the drive home again, he still had to do his homework anyway.

He’d collapse into bed every night, “dead tired.” “It was a stressful time,” he says, and he looks knackered parroting out the timetables, just as he does the best part of an hour later when he recalls a gruelling routine that would take him from London to Hanover to Wolfsburg and back over 36 hours whenever QPR’s schedule permitted it.

Puberty would change Polter. He had not only started to grow, but he was shedding his shyness at the same time. He only really had a couple of close friends as a kid. He was quiet, insular and unsure of himself. But Bremen had helped that, at least. He was growing more confident, louder, brasher. And he couldn’t stop talking, saying whatever came into his mind.

Now, his voice is as deep as the ocean. When he stirs his cappuccino the spoon looks absurd, tiny in his hands, but it’s only on listening back to our interview that I realise the noise it makes. He clanks it around like a spade in an oil drum. His eyes are piercing blue, his nose is pointed in a Ron Wood sort of a way, he has a scratchy, patchy chin beard.

His thighs are huge. They could be the bulwarks designed by Isembard Kingdom Brunel for The Great Eastern, when it was built at the heart of the industrial revolution, the largest ship on earth, but they are hidden now. It’s at training, or after a game you notice them.

When the floodlights come on at the Alte Försterei his shadow can cast an entire penalty box into darkness, but here, sat at an oversized table, he looks more normal sized, more human.

Those thighs are the product of a long summer spent running up endless flights of stairs. Up and down, up and down. Taking thousands of shots with his stronger right foot, and then a thousand more with his weaker left. He had made the fearless decision to hang up his gloves, even though there were people who said he was stupid to waste his talent and his opportunities so simply like that. But he wanted to be a number nine. And Polter knew a striker had to be fitter than a keeper, and he had to adjust.

He would watch all he could of the wonderful Brazilian centre forward Ronaldo. A scorer of goals with both feet, and with his head. From whatever angle, whenever the chance came. There are those who will tell you Cristiano Ronaldo is the best footballer to ever play the game. They are wrong. He isn’t even the best Ronaldo.

Ronaldo was once dismissive of his mum when she said he was born to score goals, but it was hard to watch him play with such intuitive genius and come up with a different conclusion. There were few fourteen year olds in the world who didn’t want to become a striker too having seen him the first time.

Polter scored five against Osnabrück II in a 5-2 win on debut when he returned as a reborn striker for Wilhelmshaven. It was his first game back since Bremen. “After that they were all quiet,” he says with the wide grin on his face of a man proved right in the face of everyone who’d said it was a mistake. He scored 69 goals that season. That he “enjoyed every single one” is clear. He sticks his tongue out through his smile as he says it.

Polter made his biggest leap into the dark when he signed for Braunschweig a couple of years later. He was still just 16. A boy. Alone in a flat with two other youth players, a couple of years older than him, he had to cook and to do the washing up. He had to clean and to get himself to training and back. And he had to avoid the infinite opportunities available to a young man away from home for the first time. He was lucky. His family would come and see him. His flat-mates told him to wise up, to not waste his opportunity. They told him he was good, but that being good was never enough and never would be.

Not even if you were as good as Ronaldo.

There are players for whom football is just a job, a slog, a chore like every other idiot in the world has to put up with, day in, day out. It’s a natural consequence. But to him, apart from his family, it is everything. On the night after his most lauded goal, he stayed up all night playing the new FIFA.

He looks out of the window from the lounge we are sat in, over the empty pitch towards the Gegengerade, as he remembers his home debut at the Alte Försterei. He’d not performed in his first game, away at Heidenheim, and he knew it. Union lost 3-1, and it left them in the bottom three. Polter wasn’t yet wearing the number nine he would always covet yet.

But he’d had the benefit of an international break to get ready for the visit of RB Leipzig. He’d had ten days of unbroken training with his new team-mates, learning how they moved and how they thought. Or as he puts it, “the team had to get used to me, as I had to get used to the team.”

And he was determined to make a difference against a club he says he will never understand. Even compared to Wolfsburg, who he joined under Felix Magath as champions. “You have to keep a lid on things, as a player, but I understood the protests, sure.” It’s pretty rare to find players who’ll say this sort of thing, even at Union. After all, this is their career. They see the world differently to fans and they never know where they’ll end up next.

But he wants you to know that were he not on the pitch, then he’d be in the stands, dressed in mourning black like they were that Saturday afternoon. And it was a beautiful, strange day. 21,000 people with almost as many thousand black bin liners laid out on the terrace to be donned as robes, the sun occasionally flashing off them, rustling like the leaves in the Wuhlheide on a windy day. Christian Arbeit addressed the fans in an angry, yet funereal tone. And a sea of banners in the crowd proclaimed the death of the people’s game.

“Football needs emotion… terraces… passion… history… independence.”

The terraces filled and so did the press box. Every available spot in the stadium was full. Everyone thought they knew that RB were going to walk the league, and wanted to get a look in, a piece of the new action. The away end chanted “Hurra, hurra, Sachsen ist wieder da”, and the Unioner chanted “Alle Bullen sind Schweine,” in retort.

But then they went silent. A protest where the fans took back the only thing they had to give: their voices. It was like a total eclipse of the sun with the confused barking of dogs replaced by the confused shushing of all those Unioner, stifling every natural impulse to cheer, to chant, to tell these bastards that the game belonged, not to they, but to the team with their new loan signing, Polter, up front.

After 15 minutes they erupted. The noise was like a hurricane had just blown in. Ticker tape rained down like it was Neil Armstrong out there. And Polter looks out of that window, reminiscing, as if he is back out there in front of it all, “I knew immediately I would give everything for Union…” before trailing off in a reverie.

But it took a while, still, for him to get into the game. He couldn’t quite reach a high ball from Eroll Zejnullahu. A through pass from Benny Köhler was just over-hit. Sören Brandy, a player in the number nine shirt he coveted, but with whom he would form a wonderful partnership that season, sent him through with a beautiful pass, but Polter’s first touch was heavy. He had to chip Benjamin Bellot in RB’s goal, but his shot sailed over. Polter dragged his fingers through his hair and ran back into place. They’d been playing for an hour, and this was Union’s first good chance. There were niggly fouls all over the pitch.

Flicking back through my notes of the day, the names read like hastily scribbled ghosts of the past. Names that seemed so comforting. Sören. Benny. Eroll. Björn. Baris Özbek flattered to deceive as always. He’d play a great pass, make a raking tackle, before somehow drifting off, looking at his all too beautiful shadow whilst the game went on around him.

Then it happened. Polter won a free kick on the left. He hit it firmly across the goal, hoping it would beat Bellot’s outstretched left hand. It did. Just. The Alte Försterei roared his name for the first time and he revelled in it for a moment.

Polter was the best man at the wedding of Toni Leistner. It is unrecorded if he mentioned during his speech the fact that Leistner gave the ball away for Yussuf Poulsen to equalise that day, but it’s unlikely. Because despite the fact that the Dane was the best player on the pitch, the stars were shining only for Polter. He swept onto Fabian Schönheim’s pass like Fred Astaire onto a sound stage at MGM, and finished with aplomb. The winner. 2-1.

It took Damir Kreilach to come over to break up the party after that goal. We’ve still got to focus, he said. But Polter would be taken off within five minutes anyway. He was done.

When Magath started to introduce him into the Wolfsburg side he didn’t know where to put himself. Here he was, like that pre-pubescent, shy kid all over again, looking at great strikers like Grafite and Dzeko and Mandzukic. He says he just “kept my mouth shut,” and he tried to learn from all of them their art. “Dzeko was always a player I watched… What’s he doing? How does he move, How is his first touch… he was strong, robust… I took loads of tips from him as a player.” But his goals, like Richard Hell’s wonderfully dirty love, only ever came in spurts. For Wolfsburg he scored in consecutive games against Stuttgart and Köln. Then for Nürnberg he scored against Hoffenheim and then a fortnight later against Fortuna. But it never really happened for him in the Bundesliga, at Braunschweig or Nürnberg, at Mainz or Wolfsburg.

https://www.instagram.com/p/iEjZu7wuv6/

He’s asked the same question all the time, he says. People want to know why, when the truth is just so mundane. It was hard, and he was young, and he’s self aware enough now to say so. “Maybe I just wasn’t ready.”

But by the time he arrived at Union in 2014 it looked like he now was. It wasn’t the goals against Leipzig that showed his ability to play as a gorgeously old fashioned centre forward. It was his winner against St. Pauli at home that year, coming as he chased down a ragged pass from Sören Gonther to the keeper, Robin Himmelmann, and scored with practically the last kick of the game. It was as if everybody else had given up that evening. They were ready to go home for the weekend, but he sniffed blood. He rolled the ball past the keeper with a childlike joy.

In its wilful refusal to accept defeat it was, actually, a very Ronaldo kind of goal. He played with an unquenchable thirst, and he never, ever needed two chances.

But whereas Polter’s header in the last minute against Pauli a couple of years later in front of the Waldseite was similar in timing, it was borne of a different school, it was much more English in its delivery. He hung in the air as defenders bounced off him. He kept his eyes open all the time, his shoulders back, his back arching for maximum power.

This was a Nat Lofthouse goal, the number nine he reminds me most of. Their haircuts are similar, short back and sides with ruler straight side parting, as are their builds. Six foot tall, balanced on those huge thighs like the Colossus of Rhodes. And they say their demeanours are, too. I will never know. I, like every English football fan, just know the legends.

Lofthouse remains one of the defining English centre forwards. He was strong with both feet, was one of the best headers of the ball ever to play the game. He also improved as he aged, having initially struggled to make the step up from the wartime leagues. He scored the last minute winner against Austria in 1952 being knocked out cold in the process. He collided with the goalkeeper Josef Musil, and only knew he’d scored when he was revived a twitchy and worrying minute later.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BNEYSQphFom/

It is stories like this that made Polter want to go to England. He’s open about it now, and always was, saying that if he ever got the chance to go to the home of football he would. Like a shot. It would mean he could learn more, too, about this old fashioned art form. About holding the ball up. Playing with your body as well as your feet, with your back to goal. You have to drop deep and look for the ball. And you have to fight. The 2.Liga is trickier, more complex and technically better, he says, but when it comes to that stuff, the English are miles ahead.

As they should be. Lofthouse defined the artform of the classical number nine 65 years ago.

Many fans grew to love Polter at QPR, as he adored the city, but he couldn’t hit the back of the net enough. He loved the fans back, and the league and the romantic idea of being surrounded by all that footballing history, as they appreciated his work ethic and saw that he was improving, as was his English.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BIptT_ZAPKC

But he couldn’t settle properly, and he kept thinking about home, about his kids. It was tearing him apart. “When you can’t see your kids every day, you’re missing something. The strength I showed on the pitch, I got from my kids. When you come home every day and see their smile…”

Sebastian Polter is a walking mess of contradictions in many ways. He’s a shy man in a boisterous, big, beaming body. A gentleman who thrives off intimidating defenders. A goalkeeper who wanted to be a number nine.

Sometimes, before he catches himself, he says he feels an overwhelming responsibility for his team-mates, noting the amount of money the club spent on him, too. “I have a duty as a leader, which I am, and a duty to help the team,” but he says he’s also not alone on the pitch. It’s not all up to him. It can’t be. No man is an island, after all.

There is a certain tension that he says every player feels. Nothing on earth can compare to it, it’s a heightening of the senses, but he’s never been scared before a game, he wasn’t as a kid and isn’t now. “I’m scared of death, not of playing football.”

He wants to do it all, but he can’t. He wants to just play with his mates but he feels a weight on his shoulders.

All of this (for want of a better phrase we shall call it the duality of Sebastian Polter) was summed up by an hour or so of playing time spread across two games that couldn’t have been more different, a couple of years ago now, after he’d come back from London.

He’d been dropped for Sandhausen away. Polter festered on the bench for over an hour, and he watched on impotently as Union were outfought and out thought and could have played for another five hours and not scored.

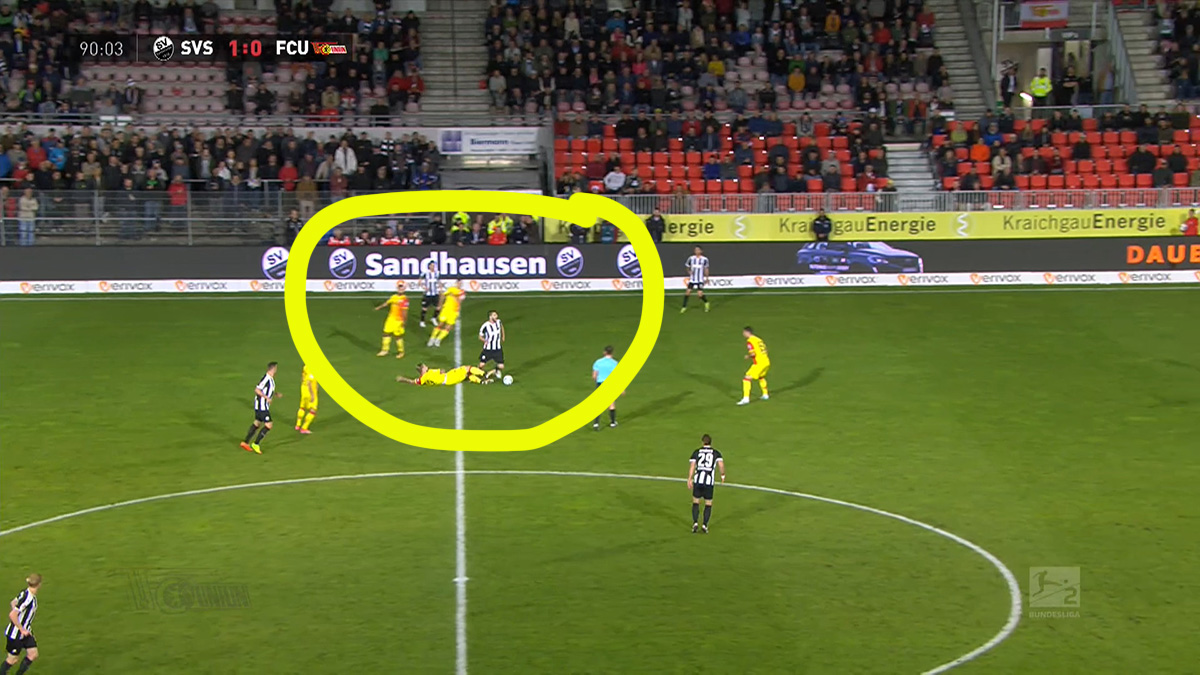

But when he came on he couldn’t affect the game any more effectively on the pitch than he had off it. It sometimes happens like that for him when things aren’t working. He looked like his focus was directed in all the wrong places. For 20 minutes he chased about, and then with a minute to go, as all hope was over, he got booked for a horrible late challenge when he lunged from behind, clattering Sandhausen’s Markus Karl, pulling the world from under him. He apologised immediately, but it looked like he knew that he wanted to catch him, to get the satisfaction of boot on something soft.

He turned his back to the ref, knowing his yellow card was coming.

The curious thing was that it was as if the next five days didn’t happen for Sebastian Polter at all. The end of the Sandhausen game was just the beginning of the mauling he would dole out to an unfortunate Kaiserslautern side who were festering at the bottom of the league.

After only six minutes he picked up the ball in a mile of space a few yards outside the penalty area, and knew immediately what he was going to do with it, hitting it first time back across goal, over the keeper’s head and with enough wicked topspin imparted from his laces to make it dip like a shooting star into the far top corner. He hit it like a crosscourt winner in tennis.

Eduardo Galeano tells a beautiful story (as if Galeano would tell any other kind) about an Argentinian striker called Bernabé Ferreyra. They made him take his boots off once to make sure he didn’t keep iron bars in them, such was the brutality of his shots on goal. Polter’s first was like that. It was technically perfect, yet struck with iron booted violence.

He scored two further left footed goals that afternoon, sinking to his knees and kissing the tattoo on his wrist after the third. Kaiserslautern were bad, but he was also unplayable that day.

And in the mixed zone, the roped off corridor that leads from the steps up from the pitch to the media room at the Alte Försterei, unprompted, Polter only wanted to talk about how good Grischa Prömel had been on his debut that day, when all the journalists wanted to hear, leaning in, greeting him by first name because they all know and like him, was about his hat-trick.

Really, they expected no less.

Sebastian Polter is a striker, he hates missing out. He hates to watch from the bench, and he hates to be injured, like he was for seven, long, bastard, horrible months that stretched endlessly from the end of last season into the beginning of this. It was his longest ever lay-off and it hurt like hell. It’s not the physical pain, it’s watching your mates train. It’s going to a weights room on your own when they all file off towards the pitches with balls under their arms, taking the piss out of each other, laughing and not even noticing that you aren’t there.

It was like being 13 again with his dad pushing him on up and down those stairs.

Then, two days before the visit of Holstein Kiel to the Alte Försterei, Urs Fischer asked him if he felt good enough for maybe fifteen minutes at the end. He didn’t ask anything else of him. He didn’t say he’d need him to set up the equaliser. Or score the winner. He just asked him if he was ready. It would be like his home debut against RB again, for there would be a protest, 20 minutes of silence this time, and he would still have to hold his tongue. But eventually he got his chance and he was greeted onto the Alte Försterei pitch with a cacophony. They’d missed him, too.

But nobody believed what was going to happen. It was 0-0, but the entry of Polter changed all the dynamics on the pitch. His eyes were burning with determination. He set up the goal to put Union in the lead through force of will alone, it seemed.

And then?

Polter burst onto a threaded Marcel Hartel pass into the inside left channel, and clipped the ball not quite high enough to clear the keeper, Kenneth Kronholm. No one else saw what was coming, but the ball rose into the air, up behind Polter who was already turning, his eye on it all the time as it dropped back over his shoulder. He was already in the air as the crowd noticed what was going on. He was in slow motion, twisting, rising, contorting those huge thighs. Hitting the ball cleanly, perfectly. It looped in an arc over Kronholm’s despairing arm.

It felt somehow pre-ordained. Like it was meant to be. Within seconds he had half of his team on his back as he stood there, taking the weight, enjoying the pandemonium going on in front of him in the Waldseite. His mates were all in the stands, seven or eight of them, they’d all come when they knew he’d get a run out.

He’s got a huge framed photo of his comeback goal against Kiel at home on his wall, but he looks around the room to see if there’s one here as well. He can hardly believe that there isn’t. His has a caption with the word “comeback” in English on it. But it could have quoted Curtis Mayfield, so astonishing was the moment.

The man of the hour

Has an air of great power

The dudes have envied him for so long

He’d scored a bicycle kick once before, against Cottbus in the cup for Wolfsburg II. It was, as far as he remembers, up til now the only one he’d ever scored, and it too was in the running for the Sportschau goal of the month. It came third. Julian Draxler won with a goal that was the half of Polter’s. But he liked how it felt to hang in the air like that, in control. And how the ball came off his laces perfectly. He never bothered practising them though. Not really. The chance comes only so rarely in real life. “And it’s twice as difficult to score one in the 2.Liga as it is in the Regionalliga… you really can’t compare the two.”

You can tell his earliest influence in football was Oliver Kahn. “He was a player who always said what he thought, and that’s what I still do.” He’ll be the first to tell you that he has never been very good at hiding his true feelings, and it’s something he’s had to work on since he became a dad himself. Now he feels the dull throb of responsibility every waking hour telling him that he needs to make sure his kids grow up balanced and measured in a way that he thinks he is not. Everything he does, he says, is done with his kids in mind.

It’s why he had to come back in the end. They are four and six, living with his ex in Wolfsburg. He sees them every fortnight but it’s really not enough. It never is.

https://www.instagram.com/p/ukehE3wut5/

“I’ve become a bit quieter since they were born. I was always having fun, of course. I’m a man who engages his mouth before his brain. But with kids you have to do things the other way around. You have to teach them, advise them. You have to ensure they can be successful… And as a father you’re responsible for that. I’m wiser, more aware. There’s things I’ll say in the changing room that I’ll never say in front of them.”

He takes his role seriously, for his kids, for all those who look up to him. But he’ll never be able to block out the garrulous and brash striker that the shy kid from Wilhelmshaven grew up to be. When we meet, he’s wearing a baseball cap, hand stencilled out of red, white and yellow paint with a capital “P” and a number nine on it. He doesn’t need to explain what they mean, but he does so anyway.

He talks to everyone on his way around the stadium. Joking, laughing, winding them up, pulling faces behind their backs to make others laugh. He bumps fists and he shakes hands with the waiting staff and the press people, the cooks and the cleaners.

And watching it I remember a quote about Lofthouse, that great old English number nine, from David Winner’s masterpiece of a book, “Those feet”, that works curiously well for Polter too.

“It’s pride. He is them. He is the best of them. He’s the club as far as they are concerned.”

He’ll never be as good as Ronaldo, or Lofthouse, or di Stefano or Batigol, of course. No-one will. But he is a man completely at home here, at Union. Sebastian Polter is a striker. The king of his castle.

Entdecke mehr von Textilvergehen

Melde dich für ein Abonnement an, um die neuesten Beiträge per E-Mail zu erhalten.

Beautiful!

Wow. I really enjoyed reading this. I love your ability to paint pictures with words, even though I always have to use a dictionary to fully understand you. This one, of course, is not as epic as the season review you wrote in 2017. But still, after having read this text, I feel like leaving a movie theater after a great movie.

So thank you.

And never forget…

[…] Ein bisschen ist es wie eine Biographie. Vor allem lernen wir, was Sebastian Polter wichtig ist. Den Text könnt ihr auch im Original auf Englisch lesen, wenn ihr […]